Updated on: January 27, 2018

Despite the difference in price and sensor size, the Sony A9, the Olympus OM-D E-M1 II and the Panasonic G9 are all good examples of how mirrorless technology is evolving, especially concerning the improvements in speed and the electronic shutter. The latter in particular hints at a future where cameras may no longer require mechanical curtains at all.

But what is an electronic shutter exactly? Well, let’s rewind just a little.

Ethics statement: We were not asked to write anything about these cameras, nor were we provided any compensation of any kind. Within the article, there are affiliate links. If you decided to buy something after clicking the link, we will receive a small commission. To know more about our ethics, you can visit our full disclosure page. Thank you!

[toc heading_levels=”2″]

Article updates

- January 27, 2018: added thoughts and considerations about the Panasonic G9 following the beginning of our in-depth test with the camera

Mechanical vs Electronic shutter

By default when you take a picture with a mirrorless camera, there are two mechanical curtains that open and close in front of the digital sensor, exposing the pixels for the duration you select (shutter speed).

Below you can see a slow motion video of the mechanical shutter of two cameras (Sony A7r II and Fujifilm X-T2) in action.

An electronic shutter mimics this movement by powering the pixels on the digital sensor for the amount of time required (shutter speed).

There are different types of electronic shutters: the global shutter – used in high-end digital cinema cameras – can activate all the pixels at the same time. The rolling shutter – found in mirrorless, DSLR and most digital cameras – reads each row of pixels one after the other. Put into different words, imagine a scanner analysing a photograph: the sensor goes from one side to the other in order to capture the image. The electronic shutter works in a similar way in that it “scans” the light coming through the lens.

The e-shutter has been around for years. At first it mainly proved useful to avoid vibrations caused by the mechanical curtains and for silent shooting. I had the chance to work with some of these cameras at contemporary dance shows where scenes lacking music were common and as you can imagine, silence was mandatory. Usually photographers put a special cover over their DSLR to reduce the noise and wait for the music to begin again before taking the shot. In my case, I was free to hit the button whenever I wanted, which was a nice advantage.

Then we started to see other improvements such as being able to go beyond the fastest shutter speed of the mechanical shutter. Brief exposure durations like 1/16000s and 1/32000s became possible on many cameras, allowing you to use very fast apertures in bright sunlight for example.

However the electronic shutter also introduced some limitations. Some of them are minor and they vary from model to model:

- some high ISO values may not be available

- the bit depth of RAW files decreases

- the slowest shutter speed available can be shorter

On the latest models, many of these issues have either been fixed or are being improved.

Then we have more important issues like distortion and banding. These are also common for movie recording because the camera uses the e-shutter for videos by default.

Distortion (also called rolling shutter effect) happens because the camera isn’t able to “scan” the sensor quick enough when fast movements are involved.

Banding (also called flickering) can happen with high frequency artificial lights (fluorescent lighting for example). It creates different brightness intensities and colour bands across your image. A different shutter speed can solve the problem in some cases but not always. Sometimes banding can be clearly visible in the EVF or monitor but other times it becomes harder to detect like in the example below.

However, some of the most recent cameras like the OM-D E-M1 II, Sony A9 and Lumix G9 have a faster sensor readout, making the electronic shutter a more viable alternative to traditional mechanical shutters than ever before, and allowing the brands to push other features such as continuous shooting to new levels.

Is the electronic shutter the future of mirrorless cameras?

Let’s try to answer this question by analysing these three cameras a little more closely.

Olympus and the evolution of speed

The Olympus OM-D E-M1 II was the first mirrorless camera I was able to use with the electronic shutter and witness minimal to no distortion whatsoever. The question is: why give priority to the electronic shutter over the mechanical shutter? In this case, the answer is speed. Thanks to its quad-core image processor, the camera can shoot up to 60fps in High mode with full-sized 20MP RAW files (AE and focus are blocked on the first frame) and 18fps in Low mode with continuous AF.

Below you can see a compilation of images shot at 60fps with the Pro Capture mode (more on this below).

Olympus’ goal was to give photographers a very fast camera capable of capturing the perfect moment. Speeds as fast as 60fps might seem excessive, but in certain situations they can be useful to capture certain types of action, such as the arrow hitting a water balloon in the example below. Some photographers have also emphasised its use for certain types of studio work such as throwing coloured dust or water on a model and I can certainly see how helpful it could be for wildlife photography.

The camera includes another interesting feature called Pro Capture that takes advantage of this stunning speed. When you half-press the shutter release button, the camera starts to pre-load images into its virtual memory (buffer) so that when you fully depress the button and start shooting, up to 14 images can already be written to the memory card. This helps you reduce the chance of missing the perfect moment.

I tried this feature during a football game where my aim was to capture a player hitting the ball with his head. Of course, an experience sports photographer would be able to take a similar picture by knowing the game and anticipating the action but for someone like me who doesn’t shoot sports on a regular basis, I find it quite useful.

Pro Capture is interesting for another reason: even though the latest electronic viewfinders have a very short time lag (0.006s on the E-M1 II), that small delay between what’s happening and what you see can still make a difference with very fast action. Because the Pro Capture mode lets you save 14 images before starting to shoot, it overcomes that small drawback.

Note: Pro Capture only works with Olympus Micro Four Thirds lenses.

What about distortion? Well, most of the time when using the camera for sports or wildlife I didn’t notice any relevant issues but it isn’t 100% free. For example, in the image below, you can notice some minor distortion along the vertical lines but it is less severe than with the Fujifilm X-T2 image seen before.

The vertical lines are ever so slightly distorted in this case.

If you don’t feel you can trust the electronic shutter at all times, the E-M1 II features excellent continuous shooting speeds with the normal mechanical shutter as well (15fps and 10fps) which makes it a good hybrid solution between the safety of the mechanical shutter and the extended performance of the electronic shutter.

Sony and the evolution of live view

The Sony A9 doesn’t reach 60fps but it can do 20fps with AE and AF tracking which is a little better than performance of the E-M1 II in Low burst mode. We also need to take into account that the A9 has a larger sensor (35mm vs Micro Four Thirds) and slightly more megapixels (24MP) which means there is more data to process.

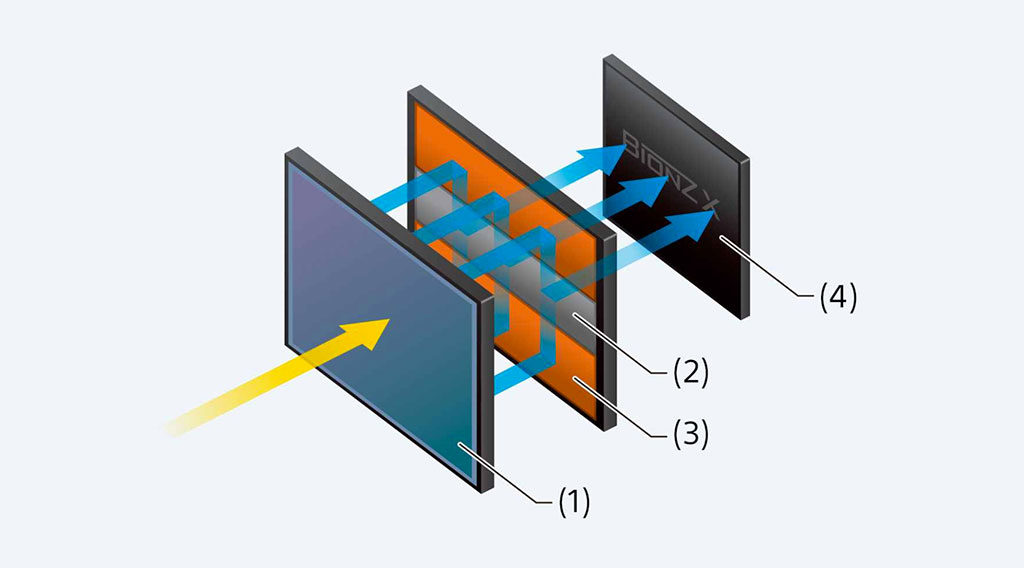

To give more power to its new flagship camera and allow for this kind of performance, the company included a special sensor with a stacked memory to increase the processing capabilities. The result is 20x more speed in comparison to the second generation of A7 cameras.

Besides the burst speed, there is another aspect that makes the A9 very interesting: live view with no blackouts. To understand why this is an interesting point, let’s analyse what happens inside the electronic viewfinder (or LCD monitor) when taking a picture.

First we have live view: the camera captures and processes a continuous image feed from the sensor that is sent to the small electronic screen inside the viewfinder or the rear monitor of your camera. This allows you to preview your composition and make the necessary adjustments before taking the shot. Live view can be displayed at different refresh rates (frames per second) depending on the settings of your camera. 60fps is the standard nowadays but some cameras can go up to 120fps (the E-M1 II and A9 are two of them). The faster the refresh rate, the more fluid your live view is.

Now what happens when you hit the shutter release button?

With the mechanical shutter and the up-and-down movement of its curtains, you see the EVF or rear screen go black for the time corresponding to the selected shutter speed (which is usually very brief unless you’re taking long exposures). With the video at the beginning of this article in mind, here is how it goes:

- the first curtain comes down and covers the sensor while the latter resets, EVF goes black

- the curtain goes up and exposes the sensor to the light

- at the end of the exposure time the second curtain blocks the light and ends the capture of your photograph

- the shutter re-opens and the camera resumes live view while finishing to process the image.

With continuous shooting, multiple blackouts will appear inside the viewfinder and what I just described above happens continuously. In other words, live view is constantly interrupted by blackouts during burst shooting.

Below you can see an example of live view with blackouts on the OM-D E-M1 II at 10fps (mechanical shutter).

With the mechanical shutter, some mirrorless cameras are capable of showing a live view with blackouts up to 8fps or 10fps but most products can’t go higher than approximately 3fps to 6fps. What happens if you select a faster speed? Well, in that case, they display the last picture taken instead. This solution get rids of blackouts but introduces more delay between what is happening and what you are seeing for two reasons:

- there is no real time view anymore, the moment you see just happened a split-second before

- you see a succession of images that correspond to the continuous shooting speed selected. So if you are shooting at 8fps, you will see an 8fps playback of the images being recorded.

As a result, following a fast subject that moves in an erratic way becomes more difficult.

Ok, so what about the electronic shutter then?

Well, because the electronic shutter doesn’t deal with mechanical curtains, it can potentially solve the problem of blackouts but there is still the live view issue. Most cameras can’t process continuous live view and image capture at the same time because it requires more power, or if you prefer, more processing speed. For example, the E-M1 II shows you a live view at 18fps with the e-shutter but you see blackouts because the sensor is being reset between each shot. In other words, the video feed to the EVF/LCD is temporarily blocked so that the camera can record the image.

The clip below shows you live view on the E-M1 II at 18fps with the electronic shutter.

So now you should have a clear idea why the A9 brings something new to the table.

Thanks to its stunning processing speed, the Sony has more power and is able to overcome that final problem: showing you a clear blackout-free live view while recording still images up to 20fps. What’s more, the live view works at 60fps, giving you enough fluidity to follow the action. Finally, if we consider that the Sony EVF has a high resolution of 3,680k dots, which is more than the E-M1 II and most mirrorless cameras, it becomes clear that the A9 represents a large stride forward in advancement of mirrorless technology.

Below you can watch a quick video by Hugh Brownstone (Three Blind Men and An Elephant Productions) to see how 20fps with live view and no blackouts looks. Notice how the athlete’s movements are fluid in the monitor. It’s like recording a video.

The blackout-free live view of the Sony A9 makes a relevant difference for fast action, which is something I particularly appreciated for birds in flight. You can more easily follow your subject and as soon as it changes direction, you react more quickly because what you see in the EVF is in real time without any kind of interruption or delay. Furthermore, tracking the bird is easier because there is no lag when you start shooting, so there is a smaller chance of momentarily losing sight of the subject and having to recompose. Indeed, it can be hard to go back to another camera once you’ve tested these capabilities.

Concerning distortion and banding, the camera behaves really well. I took numerous pictures at an evening football game and of birds in flight using the electronic shutter and I didn’t come across any relevant problems. Although I didn’t have the chance to compare the A9 to the E-M1 II, my impression is that the Sony is superior to the Olympus camera when it comes to the speed of the sensor readout.

One advantage Olympus maintains is speed with the mechanical shutter. If for some reason you don’t want to use the electronic shutter, you are limited to 5fps with the A9.

Panasonic G9: trying to get the best of both worlds

It was only a matter of time before we saw another mirrorless camera claim similar specifications to the two seen above. The Lumix G9 can shoot at 60fps (AF locked on the first frame) or 20fps with AE/AF tracking when using the electronic shutter. Its viewfinder has a high resolution of 3,680k-dots, an impressive 0.83x magnification and a refresh rate that goes up to 120fps.

The official press release, as well as some initial reviews, mentioned a blackout-free EVF on multiple occasions which hinted that the G9 could have very similar capabilities to the A9 described above. To be 100% honest with you, it is what we initially believed as well. However there is an important difference that puts the Sony camera a step ahead of the G9.

Although it is true that, at 60fps and 20fps, the Panasonic doesn’t have any blackouts in the EVF, this is only because there is no live view. The last image taken is shown instead which means that what you see has already happened. Unlike the Sony A9, there is a initial delay caused by the live view feed being interrupted when you start taking pictures with the G9. The Lumix doesn’t have enough power to maintain uninterrupted live view and further proof of this is seen when using the e-shutter at 9fps: there are blackouts just like on the E-M1 II.

So talking about a blackout free EVF without mentioning live view can be misleading because the “last image taken” solution has been used on cameras for years. For example, the OM-D E-M5, which was released in 2012 and is capable of 9fps, uses the same technique, so we could say that the original E-M5 is blackout-free as well.

With that being said, the G9 solution does offer an advantage over the E-M1 II. Once you get past that initial lag at the beginning of a burst, seeing the last images taken at a frame rate of 20fps does help you track a very fast subject. 20fps is definitely a fast rate (close to the 24fps you see at the movies for example) and almost gives you the impression of a live view. You are not distracted by the constant blackouts that you get with the Olympus at 18fps or when using the G9 at 9fps with or without the electronic shutter. So there is definitely an advantage once you get used to that initial lag and overall I found tracking birds in flight with the G9 easier than expected.

The Panasonic has other similar features to the E-M1 II including a Pre-burst mode which works like the Olympus Pro Capture. The buffer at 20fps is not great but it clears quickly. However my initial tests suggest that distortion caused by rolling shutter seems to be more severe than the other two cameras.

About other mirrorless competitors

I picked the Sony A9, E-M1 II and Lumix G9 for this article not only because they are three of the most recent products to take full advantage of the electronic shutter but also because they target a similar audience. Intended for wildlife and sports photographer, they include other important features like an extended battery life, faster autofocus system, larger buffer capabilities, and UHS-II cards compatibility.

While they are excellent examples of how far the capabilities of the electronic shutter have come, they weren’t the first to feature this kind of speed. To be fair, these specifications actually debuted on Nikon 1 series in 2011, which was capable of an astonishing 60fps with RAW files. Certainly the sensor and resolution were smaller (1-inch, 10MP) but it was impressive at the time.

Panasonic included a Super High burst mode at 40fps on many Lumix cameras but it was limited to JPG files and 3MP of resolution. They improved this via the 4K Photo mode which works in a different way but is based on the same idea: the camera records a video at 30fps and lets you save any of the frames as an 8MP JPG. Recently the GH5 and G9 raised the bar with 6K Photo which allows you to save an 18MP JPG. Though RAW files are missing, it is still another powerful feature that takes advantage of the electronic shutter.

Then, as explained at the beginning, we have other advantages like faster shutter speeds and the silent mode which has been around for many years now. Concerning the latter, most cameras give you the choice to turn on a “fake” shutter sound if you wish (which is generated by the camera) or leave it off. This becomes useful for sport photographers in situations where they are generally not allowed to take pictures due to camera noise. For example, British sports photographer Ian Cook has been using Lumix cameras for a while now to photograph golfers when they are on their back swing before striking the ball. (You can read more in our interview with him on MirrorLessons.)

What we must remember is that as of now, only a select number of products are capable of minimising issues like rolling shutter or banding and this is why the electronic shutter on most cameras can only be used in specific circumstances. That being said, with sensor readout becoming faster and faster, I can easily see more cameras in the future being able to replicate such performance.

Conclusion: is the future “shutterless”?

It is interesting to see that all the brands – each with its own method and technology – are pushing the boundaries of electronic viewfinders, continuous shooting speeds and other features. Indeed, whereas the main advantage of mirrorless cameras used to be their size, today it is also their technical advancements that make them an interesting alternative.

And let’s not forget that shutterless cameras already exists such as smartphones and some point-and-shoot products. However, to get rid of mechanical shutters on more advanced digital cameras, there are other things to take care of like, for example, the use of flash. Current electronic rolling shutters are generally not compatible with strobes and if they are, the shutter speed is limited to a low duration like 1/10s or 1/20s. This is where a new generation of global shutters could push the performance even further.

Certainly it is going to take some time to refine and perfect this technology before it becomes 200% reliable. But once we reach a point where the electronic shutter can do everything mechanical curtains can, we could truly see the end of the latter’s long reign.

Check price of the Sony A9 on

Amazon | Amazon UK | B&H Photo | eBay

Check price of the Olympus OM-D E-M1 II on

Amazon | Amazon UK | eBay | B&H Photo

Check price of the Lumix G9 on

You may also be interested in:

- Sony A9 vs A7r III – Five key aspects analysed

- Olympus OM-D E-M1 vs OM-D E-M1 II – The complete comparison

- Olympus OM-D E-M1 II vs Fujifilm X-T2 – The complete comparison

- Panasonic GH5 vs OM-D E-M1 II – Five key aspects analysed

- Best mirrorless cameras for wildlife and bird photography