The most natural point of comparison for the recently released Panasonic Leica 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0 is the only other high-end wide angle zoom for Micro Four Thirds, the Olympus M.Zuiko 7-14mm f/2.8 PRO. (In fact, it was the very first comparison we published after receiving the Panasonic zoom to test.)

However, those drawn to the Leica’s versatile zoom range may also find themselves wondering how it compares to another wide angle zoom for the system with an almost identical range of focal lengths: the Olympus M.Zuiko 9-18mm f/4.0-5.6.

Before we begin this comparison, it is important to keep in mind that we are dealing with two very different lenses with equally different target audiences. Whereas the Leica is a premium product with a price tag and build quality to match, the Olympus is not only the least expensive wide-angle zoom for the system but also the most compact.

Ethics statement: We were provided with samples of the Panasonic Leica 8-18mm and Olympus 9-18mm for a three-week loan period. We were not asked to write anything about these products, nor were we provided with any sort of compensation. Within the article, there are affiliate links. If you buy something after clicking the link, we will receive a small commission. Don’t worry – the price remains the same for you. To know more about our ethics, you can visit our full disclosure page. Thank you!

[toc heading_levels=”2″]

Main Specifications

Leica DG Vario-Elmarit 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0

- Mount: Micro Four Thirds

- Focal length: 8-18mm (16-36mm in 35mm equivalent terms)

- Lens configuration: 15 elements in 10 groups (3 aspherical lenses, 2 ED lenses, 1 aspherical ED lens, 1 UHR lens)

- Lens coating: Nano surface coating

- Angle of view: 107° (wide) or 62°(tele)

- Minimum focusing distance: 23cm

- Magnification: 0.12x

- Aperture blades: 7 circular diaphragm blades

- Aperture range: 2.8 to 22 (wide) or 4 to 22 (tele)

- Filter diameter: 67mm

- Weather-sealing: Yes (dust, splash and freeze proof)

- Optical stabilisation: No

- Dimensions: 88mm x 73.4mm

- Weight: 315g

Olympus M.Zuiko 9-18mm f/4.0-5.6

- Mount: Micro Four Thirds

- Focal length: 9-18mm (18-36mm in 35mm equivalent terms)

- Lens configuration: 12 elements in 8 groups (3 aspherical lenses, 1 ED lens)

- Lens coating: N/A

- Angle of view: 100° (wide) or 62° (tele)

- Minimum focusing distance: 25cm

- Magnification: 0.1x

- Aperture blades: 7 circular diaphragm blades

- Aperture range: 4 to 22

- Filter diameter: 52mm

- Weather-sealing: No

- Optical stabilisation: No

- Dimensions: 56.5mm x 49.5mm

- Weight: 155g

Design and Ease of Use

Both the Panasonic Leica 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0 and Olympus M.Zuiko 9-18mm f/4.0-5.6 are variable aperture wide-angle zooms. The former has an equivalent range of 16-35mm in 35mm terms whereas the latter has a slightly more restricted range of 18-35mm in 35mm terms.

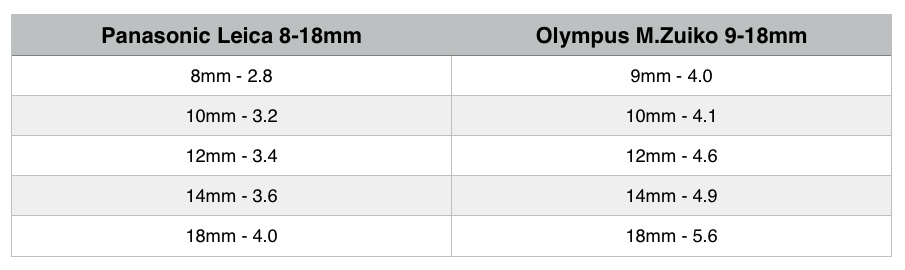

The aperture changes that occur on the two lenses are as follows:

The length of the Leica lens never changes because the front element moves back and forth inside the barrel while zooming. This contrasts with the Olympus whose lens system retracts into the barrel for storage purposes and extends when in use. Extending the lens is achieved by simultaneously pushing the release switch on the barrel and turning the zoom ring.

The Olympus is approximately half the weight of the Leica and half the height when the lens system is retracted into the body, making it the easier of the two to pack and transport. If you extend the barrel of the Olympus to its full length, it becomes just a few millimetres shorter than the Leica.

Whereas the barrel diameter of the Olympus lens is the same size as the MFT mount, the Leica’s barrel is thicker and thus extends beyond the base of some of the smaller Micro Four Thirds bodies.

Adding to the length of the Leica is its twist-on petal-shaped lens hood which comes packaged with the lens. Although there is a dedicated lens hood for the Olympus lens (the square-cut LH-55B), it must be bought separately.

Usefully, both lenses feature a filter thread for ND filters. The Leica’s is a 67mm type whereas the Olympus is a 52mm type.

In terms of build quality, the Leica is the more robust of the two. Not only is it constructed of a mix of metal and high-quality plastics but it is also dust, moisture and freeze proof down to -10°C. It comes with Nano surface coating to mitigate flare and ghosting. With the exception of the metal mount, the Olympus is mostly composed of high-quality plastics and does not claim any sort of weather resistance or lens coating. That said, it feels solid and well-made.

Both lenses feature zoom and fly-by-wire focus rings with a ribbed design to give you a better grip. Next to the zoom ring, you’ll find the most important focal lengths.

I personally find the Leica’s focus ring easier to use because it offers more resistance and extra precision when making very fine adjustments to focus. The Olympus’ focus ring moves a little too freely by comparison.

The Leica is the only one to feature an AF/MF switch on the side of the barrel. To switch between AF and MF on the Olympus, you must enter the camera menu.

Both lenses come with a standard clip-on lens cap.

Optical Quality – Through the lens

If you are reading this comparison, the aspect that most likely concerns you is the difference in optical quality between the two lenses. Since it costs approximately $500 more than the Olympus, we’d naturally expect superior performance from the Leica lens but let’s see if this is actually the case!

Sharpness

Let’s begin by analysing the performance at a close focus distance of around 1 metre.

Note that for the crops below, I only included the most interesting examples. Both lenses perform best between f/4 and f/5.6 through most of the zoom range and start to suffer from diffraction past f/8.

When set to 9mm and their respective maximum apertures (f/3.1 on the Leica and f/4 on the Olympus), it appears that the Olympus is ever so slightly sharper than the Leica but the differences are almost non-existent.

The performance at f/4 and f/5.6 is again very similar.

A similar tendency can be seen at 12mm, 14mm and 18mm as well. The performance is almost identical through the aperture range and at the fastest apertures.

At a distance close to infinity, this results are once again extremely similar.

If we turn our attention to the corner performance, we can see that the Leica produces consistently sharper results than the Olympus at all apertures. This isn’t to say we were disappointed by the Olympus however. On the contrary, it actually produced sharper results than we had anticipated before performing this comparison.

The only focal length the two lenses don’t share is 8mm, which is only available on the Leica lens. The good news is that the performance remains excellent at this value with sharpness peaking at around f/5.6.

Bokeh

Getting a pleasant bokeh out of a wide angle zoom is anything but a walk in the park, especially when the lens in question lacks a fast constant aperture, but it is possible to achieve some interesting results by taking advantage of the closest focus distance and finding a nice background.

In the case of the Leica and Olympus, it is easier to achieve a decent bokeh with the former, not only because its aperture range is faster (2.8-4.0 vs 4.0-5.6) but also because it has marginally better close focusing capabilities (25cm vs 23cm).

Chromatic Aberration and Coma

Whereas the Leica lens suffers from little to no chromatic aberration, the Olympus is quite susceptible, especially in the extreme corners. Much of it can be removed from the RAW files in post production but JPG shooters might find it more irritating.

When using the two lenses for astrophotography, we noticed that the Leica produces sharper points of light and has less visible coma aberrations in comparison to the Olympus lens. Naturally, the Leica is more practical for this particular genre because it offers a faster maximum aperture of f/2.8 at the wide end. Below you can find two extreme corner crops taken from an image of the night sky.

Vignetting and Distortion

The Micro Four Thirds system utilises software to correct certain types of lens aberrations including distortion. These correction parameters are encoded into the RAW file, so it is unlikely you’ll notice any of the lens’ native distortion as long as you use a popular RAW converter such as Adobe Lightroom that is capable of converting the files correctly. Note that these corrections are also applied in-camera to the JPGs.

For this reason, barrel and pincushion distortion won’t pose an issue with either the Leica or the Olympus in real-world shooting conditions. You may notice some minor barrel distortion at the widest angles but otherwise, the results are perfectly acceptable.

Vignetting can only be seen at the fastest aperture on the Leica (f/2.8) whereas the Olympus doesn’t display any visible falloff. Just like distortion and chromatic aberration, vignetting is easily fixable in post production.

Flare

Flare and ghosting are a fact of life on any wide angle lens due to the bulbous front element. The key to keeping flare to a minimum is to avoid strong sources of light whenever possible and to use a lens hood if one is available.

The Leica is prone to flaring but less so than other Panasonic Leica DG lenses I’ve tried in the past, whereas the Olympus appears to be quite resistant. Below you can see a couple of the worst examples I encountered during our testing period.

Purple “blob” flares can occur with both lenses on Olympus bodies but you can usually eliminate them by adjusting the composition by a few millimetres.

Field of View

When set to their longest focal length of 18mm, we noticed that the Leica produces a slightly wider angle of view than the Olympus. At 9mm, their field of view is far more similar.

Something from which only the Olympus suffers is focus breathing, particularly at the widest angle. Focusing close will give you a slightly wider field of view than focusing at infinity.

Autofocus and Manual Focus

I’ve always been satisfied with the speed and accuracy of Micro Four Thirds lenses, and the Leica 8-18mm and Olympus 9-18mm are no exception. Even though the Olympus is one of the older lenses for the system, it had no trouble focusing in various light conditions on the Lumix GX85, Lumix GH5 and Olympus OM-D E-M1. Both also feature a very silent autofocus mechanism.

As for manual focusing, we found that the Leica’s ring was somewhat easier to use and provided better resistance than that of the Olympus.

In the case of both lenses, the number of turns required to travel from infinity to the minimum focus distance depends on how quickly or slowly you turn the ring. Specifically, it takes the Leica 1.25 of a rotation to travel the distance if you turn the ring quickly and up to 4 turns if you turn it slowly on the Leica. With the Olympus, it takes a little less than a quarter rotation if you turn the ring slowly, and a half rotation if you turn it quickly.

Note that if you turn the focus ring too slowly on the Leica, the camera doesn’t always register that it’s being turned. The opposite occurs with the Olympus – even the lightest touch will cause the focus to change.

Though Panasonic hasn’t stated one way or the other, the Leica behaves much like a parfocal lens in that the focus point doesn’t change when you zoom in and out which is useful for video work.

Conclusion

The similarities between the Leica 8-18mm and the Olympus 9-18mm start and finish with their near-identical zoom range and centre sharpness. Everything else, from their build quality to their aperture range, is quite different.

The Leica was primarily conceived with advanced amateurs and professional users in mind, which is more than amply reflected in its premium weather-proof construction, faster aperture range of 2.8 to 4.0, and superior optical quality across the frame. Because it is a professional product, it also makes more sense to pair it with larger professional bodies such as the Olympus OM-D E-M1 II or the Panasonic Lumix GH5 – though we did use it without issue on the mid-sized Lumix GX85.

The Olympus, on the other hand, remains the logical choice for beginners and enthusiasts who don’t necessarily require an extremely robust product or the very best optical quality for their photographic needs. It also makes more sense if you own a small Micro Four Thirds body such as the Lumix GX850 or Pen E-PL8, as it is the most compact of all the wide-angle zooms for Micro Four Thirds. It’s a shame that the lens hood is not provided but inexpensive third-party options are available.

Finally, we mustn’t forget that the Leica lens is approximately twice as expensive as the Olympus, and since the latter is one of the older lenses for the system, it can often be found for less than the official retail price.

As for those who already own the Olympus lens, I’d only recommend upgrading if you feel you can clearly benefit from one or more of the Leica’s extra features, such as the 2.8 aperture for astrophotography/events/weddings, the weather-sealing for landscape work in unpredictable weather conditions, or the edge-to-edge sharpness for architecture. Otherwise the Olympus is a great all-rounder and is so compact that I’ve even lost it inside my camera bag more than once!

Choose the Panasonic Leica 8-18mm if you:

- want the best optical quality possible across the frame

- often shoot in inclement weather conditions

- find the 2.8 aperture at 8mm useful for low-light work and astrophotography

- plan to do lots of close-up work and want the shallowest depth of field possible

Choose the Olympus M.Zuiko 9-18mm if you:

- are happy to do without the above-mentioned advantages of the 8-18mm

- own a small to medium sized MFT body as it is physically a better fit

- are on a budget

Check price of the Panasonic Leica 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0 on

B&H Photo | Amazon | Amazon UK | eBay

Check price of the Olympus M.Zuiko 9-18mm f/4.0-5.6 on

You might also be interested in:

- Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm f/4 vs. Olympus M.Zuiko 7-14mm f/2.8 PRO – Quick comparison

- Panasonic Leica 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0 vs. Olympus M.Zuiko 7-14mm f/2.8 PRO – Complete comparison

- Panasonic Leica 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0 vs Lumix 7-14mm f/4 – Complete comparsion

Sample Images

Panasonic Leica 8-18mm f/2.8-4.0

Olympus M.Zuiko 9-18mm f/4.0-5.6

Pen F, 1/30, f/5.6, ISO 200 – 9mm

Pen F, 1/800, f/8, ISO 200 – 18mm